Chapter 4 So you wanna…

4.1 Join the lab

We welcome applications from skilled, ambitious, and independent researchers at all levels, as long as they are burning to do good research promptly.

Undergraduate students interested in joining the lab generally need to be proficient (not brilliant) in at least one programming language, such as Python, R, Matlab, C(++), or Java, and have some biological background or curiosity in at least one research area. You should also be proficient in basic statistics.

Prospective graduate students are encouraged to review the details of the graduate program and the research described here. They may wish to consider working as research assistants in the lab to ensure a good fit before applying to the graduate program.

Rotation students must start with strong quantitative and some programming skills.

Senior researchers, research programmers, and postdoctoral fellows are also welcome to contact Sarah about opportunities for support and collaboration. We are especially looking for more postdocs to study the evolutionary dynamics of adaptive immunity.

All who are interested in joining the lab should explain in their initial communication what skills they could bring to the lab and what they hope to obtain from collaborating. It is essential to have read recent papers in the relevant research area, including some from our group, and to have an idea of the kind of questions or problems that excite you.

4.2 Do some research

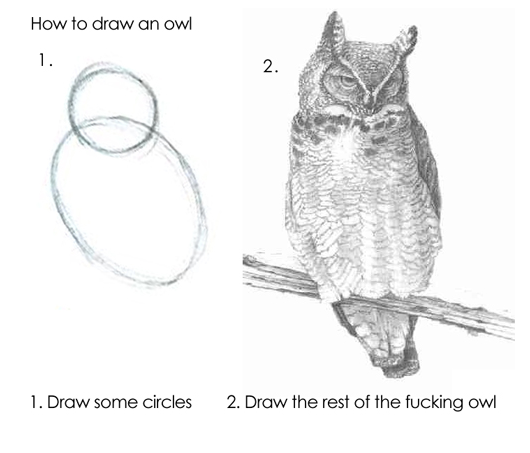

Figure 4.1: Basically, except less sequential

Identify a good question: This can take some time. Talk with other people, read, keep talking, study patterns, reason from first principles, and keep talking. What phenomena are you trying to explain? Generate many questions. Consider the next step, if necessary, in picking one.

Develop a game plan: Posit some answers to your question. What do those answers imply? What patterns or processes are (in)consistent with them? How can you test them? (And how can you make sure you’re testing them correctly, i.e., that your analysis is correct?) Draft some approaches. Prioritize a few. Add the actionable tasks to Asana. (You can keep backup ideas there too in a separate section.) Read up on project management. Sketch out the first few milestones and discuss with me. Not all projects are worth six months, three years, etc.

Set up a notebook: Create a version-controlled “lab notebook” in which to record your progress, which includes your thinking, notes from papers, and your analyses. There are many fine ways to do this: what’s most important is that the notebook is organized and that you use it. You could use Asana and Overleaf (Latex), Quarto, R markdown, or a Jupyter notebook. The last three are probably most seamless, but it doesn’t matter too much. Be sure to keep files (notes, scripts) in a repository, included in the lab’s github account. N.B. Data may need to be stored locally or in a special location, depending on its use restrictions (see below). Everything you do should be traceable and reproducible in some way—no quick “one off” figures that exist only on your laptop, or where you have to guess at which parameters or data set you used.

Think about what it would take to trust your results: How will you know if you have a bug? Can you tweak your parameters or assumptions so they match analytic expectations? What sort of reality checks can you think of, both for your model and the overall hypothesis? Write code in a modular way so that it is easy to test and debug. Elaborate inferential models should always be fitted to synthetic data first. Always plot your data and check for nonsensical values or suspicious trends. How would you know if columns or rows got swapped?

Work steadily: The point of the repository is to make it easy to save work, catch errors, roll back, and track progress. You should generally be “committing” (pushing code and new thoughts/results to) your repository at least once per day. In the same vein, you should checking off tasks at least once every few days (ideally more often). Tracking progress through tasks makes it easy to summarize weekly progress and see the next steps, which we’ll discuss in weekly or biweekly meetings.

Understand context and constraints. If you’re working with data, there might be IRB restrictions on how it can be used, stored, and shared. Your laptop might need password protection and encryption. Find out and comply. Always check that incoming data does not contain protected health information if it’s not supposed to. Also ask how the work is funded, if you do not yet know, and what kinds of reporting requirements and deadlines we may have. Contracts often require bimonthly progress reports; those for grants are less frequent. Identify any collaborators and make a plan for working with them

Have the right attitude: As long as you’re reasoning based on evidence, you’re making progress. See Schwartz (2015). Not all projects should move ahead. This is why it’s useful to step back, reassess, and discuss your work with others. Revisit and revise your previous questions.

4.3 Code well and efficiently

See the coding handbook.

4.4 Write good

4.4.1 General advice

- One of the best ways to write good papers is to read lots of good papers. This is more comfortable than learning incrementally from rejections. Additionally, there are useful books and essays on the subject (see below) that can help you avoid common mistakes.

- For grants and papers, the central challenge is to articulate an interesting question and show how you have helped answer it. Practice doing this from the beginning of your research project, as you sketch ideas and results in your notebook and share progress with others. A key insight, and the reason it’s important to read, talk with others, attend seminars, etc., is that what’s considered an interesting question varies widely by field. Learn what appeals to different audiences.

- Be clear. Use topic sentences. Assume your reader is an intelligent first-year graduate student, but with less time on her hands. Try to state things vividly and directly. Your writing will almost always improve if you try to explain your reasoning as transparently as possible.

- Focus on ideas, not people or studies. Avoid “Many studies have shown X.” Just state what has been shown and give references.

- Be consistent. If you define a parameter, refer to it the same way throughout your paper. This holds for all sorts of annoying punctuation and formatting conventions. Channel the reader’s attention into one clear, fascinating story, and let nothing distract from it.

- I like Claus Wilke’s advice about knowing, when you sit down to write, if you are drafting or revising/editing. If you are drafting, don’t worry so much about the flow. Just get the ideas down. Under no circumstances should you show me that draft, however.

- Recommendations: The Elements of Style (which I really like, contrary to Claus), “Ten Simple Rules for Writing Research Papers”, Sarnecka Lab’s “Writing Workshop”, Claire Bacon’s “Writing Tips”

4.4.2 Initial submissions

The following workflow seems to work well, but if you prefer another one, let me know.

- Write summaries of the research in your lab notebook as you go. You can probably write most of the methods and many results this way. You’ll also accumulate the major points for the intro and discussion in your notes too.

- Identify a target journal in consultation with me and coauthors. Check the journal’s instructions for authors so you know how to structure your manuscript. Note any word and figure limits.

- When it is time to write the manuscript, set up a repository synced to Overleaf. I prefer using a generic template rather than a journal-specific one, since reformatting can take precious time, and generic templates are better for preprints. Draft the figures and abstract first. Discuss the arc with me and potentially other coauthors. Sign up for a future lab meeting or theory meeting, in which we’ll discuss the complete draft (which you’ll need to distribute a week in advance). Propose an ordered author list and discuss with me.

- Next write an outline—with the main steps in the argument as topic sentences, so it’s really possible to trace the whole story—with each result in its own subsection and figures inline.

- Draft the results section. Ask another person in the lab for feedback and then revise, and then show me. N.B. I have a lamentably hard time looking past poor construction and focusing on the ideas, so I appreciate it when the writing is clear, organized, and not too laden with typos, even at these early stages.

- Next write the methods, introduction, and discussion, and revise the abstract. Do not forget to acknowledge Midway (assuming you used it), people who made helpful comments, and funders. Funders often require specific language. Investigate.

- Ask for more feedback from a labmate. Revise. Share with me.

- We’ll then discuss the manuscript in a lab meeting, and revise. Now is a good time to propose to the coauthors a schedule for your sending and their reviewing a draft.

- We only send drafts to coauthors and “friendly reviewers” when the writing is coherent and flows well. We do not want to waste their time.

- Ensure your repository is well documented and up to date, and that all the analysis—including the figures—can be run from the included code with minimal effort. We will make a “clean” (new) version of the repository public when we submit the manuscript to a preprint server, bioRxiv or medRxiv. Double check that you are not sharing protected data.

- Ask a colleague to try to run your code, given the manuscript and access to the repository, and no other help from you.

- When the final manuscript is ready for coauthors’ approval, confirm with them (if you’ve not yet) their funding and preferred and non-preferred reviewers. Make sure they don’t have a conflict of interest (COI) with any of the preferred reviewers. This typically means no coauthors, friends, or collaborators. First authors of key papers cited in the manuscript are often good candidate reviewers. Suggest at least five reviewers to limit unnecessary delays.

- Draft the cover letter, or whatever introductory text the journal requires. The cover letter should succinctly describe what is important about the manuscript (“A longstanding question is…”) and place it directly in context of other work (“To our knowledge, this is the first paper that…”) without repeating the abstract in roughly one page. It is usually good to cite the main paper your work builds on or responds to, especially if they were published in a “peer” journal.

- When all coauthors have approved the manuscript, we submit it to a preprint server (without journal-specific typesetting), publish the GitHub repository, and submit to a journal. If the work is funded by CIVIC or CEIRR, we also need to inform them of the preprint immediately.

- Ask Jessie to add the preprint as a “Paper” to the lab website. Prepare a one-sentence, lay-person summary of the main finding for us to add as a news item on the side and assign to me for review in Asana. Draft a “Tweetorial” for BlueSky or post for LinkedIn and similarly assign to me. If the work is CEIRR-funded, it should probably also be added to the Computational Modeling Core website.

- Celebrate!

4.4.3 “Mature” papers

- When you submit, add a recurring task or reminder to check on the status of the paper regularly. If it is still “with editor” (i.e., not sent out for review) at four weeks, we will email the editor. The email will go something like, “Dear Editor, we thank you for your consideration of our manuscript, ‘X.’ We notice it has not yet been sent out for review and are eager for the paper to be published. We would be happy to suggest more reviewers if it might be useful. Thank you again.” Similarly, once the paper has been sent out for review (“with reviewers” or similar), please set a reminder to check on the status at three months. We will send a follow-up email then if we have not yet received a decision.

- Ideally at least 20 min pass before we receive a decision from the journal. (That’s the fastest rejection I’ve heard someone receiving from Nature.) If we receive a rejection without review (a “desk rejection”), we might need to improve our abstract, introduction, and/or cover letter. If we’re rejected after review, we’ll take 2-3 days to consider the reviews and make a plan for revisions. Be sure to communicate decisions to coauthors, if the journal does not email them automatically, and to let the coauthors know the plan for responding to the decision.

- If the journal requests a revision, we track changes (using colored text) and write a polite and succinct reply. I like replies that are as self-contained as possible, so that months after having done the initial review, the reviewer can read over the reply and be sufficiently reminded of the context for each criticism that she or he doesn’t need to reread the whole paper. In the reply, we describe exactly what has been changed in the paper and quote the changed text (with as much context as necessary, including corresponding line numbers). Ask other lab members for sample replies to get a sense of the tone and format.

- It is to our advantage to revise quickly. With greater distance from the paper, reviewers can easily take issue with new parts. Novelty tends to decrease with time, even if nothing has been published in the interim.

- Ask coauthors in advance if they could inspect revisions and the reply during some time window—they should know when to expect our draft.

- When we resubmit to the journal, we immediately upload the revised manuscript (without journal-specific typesetting) to the preprint server. Once the manuscript is accepted, it’s usually too late to submit a revision. We would then have to decide between paying exorbitant OA fees to the journal or leaving the article behind the journal’s paywall, thereby encouraging people to access the outdated version. It’s best if the accepted version is already on the server.

- Remember that rejections and revisions are part of the game.

4.5 Email like a pro

- Be concise. Be clear if you are asking for something, or if you are simply giving information. Try to minimize the number of back-and-forths required: instead of asking if someone is free to meet next week, list blocks of time you are available and propose a location. Make it easy to reply quickly.

- Rather than send large attachments, send a link to a Box or Dropbox file.

- Be polite. Being concise is part of being polite, but being polite also means using professional titles and spell-checking your email. Striking the right tone can be hard sometimes. One error that very junior scientists sometimes make is being excessively deferential (“I was wondering maybe if you might consider…”).

4.6 Make nice figures

Mostly, see Claus Wilke’s excellent online guide, Data Visualization, and these suggestions from Sarah Leo of The Economist. Additionally, remember to

- Label your axes. All parameters should be spelled out and accompanied by their symbol (e.g., “Transmission rate, \(\beta\)”).

- Save figures in vector formats.

- If many points are plotted over one another, consider semi-transparency, adding jitter, or plotting densities.

- Minimize wasted space in figures while ensuring your axis limits are appropriate (e.g., that fractions ranging from 0 to 1 have y-axis ranges of [0,1]).

- Titles are frequently a waste of space, but be sure to include key information somewhere nearby, e.g., what the shaded area represents, how you assessed significance, etc.

- To increase accessibility, avoid relying on red/green contrasts.

- Please don’t use the default color palettes. There are better ones that indicate some thought.

- As with writing, be consistent. Use the same font sizes, styles, nomenclature, etc.

4.7 Keep up with the literature

Keeping up with the literature involves two challenges: finding papers and reading them. I’ve described what I do, but there could be better solutions.

Finding papers:

Use a RSS reader. Subscribe to major journals and bioRxiv and arXiv topics. Skim the titles and abstracts when you have a few minutes here and there. This will probably identify 90% of the new papers you might care about.

Set up Google alerts so you can get emails when particular papers and people are cited.

Use Semantic Scholar to suggest other papers that might go through alerts.

Do a good search in any area of interest so you can identify relevant papers published decades ago. It is amazing how rapidly phenomenal work can be forgotten by a field.

If the abstract looks good, I add the paper to my citation manager. I use Paperpile. Another popular citation manager is Zotero.

Reading papers:

Just block off the time on your calendar and do it.

Remember that not all papers should be read in depth. Sometimes it best to know only that someone is trying to answer question X using the general approach Y, and they found roughly Z. Other papers you’ll need to absorb. Expect challenging papers to require several passes.

Consider setting up a small reading group to discuss more challenging papers. (For easier papers, this can double the time it takes to read them.) Also take advantage of theory group and lab meetings to force these discussions.

4.8 Get funded

You’ll almost certainly have funding from me, but it’s often a good idea search for opportunities. Check with me first. Ask the grad student and postdoc coordinators, ask your peers, do searches, etc.

Work backwards from deadlines, giving yourself much more time than seems necessary, and establish a schedule. Considerations: (i) Ask Jessie if the grant will need to be reviewed by the URA and find out what their deadline is. This is the effective deadline (it’s usually one to two weeks before the submission deadline). (ii) Letter writers usually need at least three weeks before then, and it is best if you can give them a good copy of your research proposal by then too (see below). (iii) Depending on the complexity of the application, we may need four or more weeks to bounce drafts back and forth. (iv) For applications with mentoring plans, it’s especially useful to get started several months ahead, so we can identify if another sponsor should be brought on board. (v) It’s also important to start early if we’re unsure the research will be a good fit for the funder: we need the time to revise our pitch in coordination with the program officer. (vi) Many grants require preliminary data, and it’s good to figure out what that should be early.

Identify several people who will read a draft of your proposal. It’s best if some of them have been successfully funded and if they are not in your subfield. (Ideally, they’d be just like the review panel.) Ask how long they’ll need with the proposal to give you comments, and work backwards to figure out when your draft needs to be ready.

Obtain copies of as many successfully funded applications of this type as you can, ideally with their summary sheets or reviewer comments. Promise confidentiality. You can search for funded federal grants on the NIH RePORTER website. It’s also worthwhile just asking around.

Read 4 Steps to Funding in its entirety before drafting anything. It should only take a few hours. We have a copy in the lab somewhere.

Study the call/grant description carefully and study the funded applications. What consistencies appear? Potentially consult with program officers and other applicants to make sure you understand what reviewers are looking for.

Write the proposal, and get funded! No seriously, we’ll discuss proposal-specific details in person. But as a mentor once told me, people generally like things in proportion to how well they understand them, so you want to make sure the proposal is really exciting—see 4 Steps to Funding—and really, really clear. This is why we ask people outside our subfield to give us comments.

4.9 Ask for a recommendation

Remember that writing letters is part of the job for senior academics. That said, it’s important to show respect for their time.

- Ask for the letter at least six weeks in advance, if possible, especially if this is a letter for a faculty position.

- Say you’d include the research statement/proposal synopsis/relevant material by X date, where X is ideally at least three weeks before the deadline, and ask them if they would like any material sooner.

- In the follow-up email, give the writer a suggested list of points to highlight in their letter. This is your opportunity to ask them to emphasize aspects of your training or goals that are particularly valuable or nuanced, e.g., you made the key insight for a research project, the proposed research is especially novel, you were delayed in publishing because of a health problem but are otherwise fast, etc.

- At the deadline, thank them for writing. Follow up with the writer when you learn the outcome of the competition, thanking them again for their support.

4.10 See our funding

We keep copies of funded and unfunded grants in the “Grant proposals” project on Asana. Assume these grants are confidential and do not share them outside the lab. Feel free to ask me about them if you have questions, and if you write a fellowship proposal, please add your submitted proposal (excluding the budget) to the project.

4.11 Review your peers

I’m assuming you’ve already been invited to review a paper. If you’ve not, there’s not too much you can do, aside from publishing. If you make positive comments about unpublished work at a meeting, there’s a chance the authors will suggest you as a reviewer. If you make smart comments, there’s a chance editors will notice. Rest assured I’m always on the lookout for papers I can invite lab members to review with me or in my place.

If you’ve been asked to review a paper,

- Ensure you do not have a conflict of interest. Check the journal’s policy, but regardless, look in your heart of hearts, and do not overestimate your impartiality. You should decline to review papers by friends and recent collaborators. I also decline to read manuscripts that seem to be directly “competing” with my own, i.e., they are tackling the same question using similar methods. They’re probably not really competing, but if I feel they are, that’s enough to disqualify me. People often favor manuscripts by authors of the same gender and nationality (Murray et al. 2018). (There are also biases in the selection of reviewers; Helmer et al. 2017.)

- Confirm you can make the deadline. If you need more time, it’s better to ask the editor for extra time now.

- It might be a good idea to ask if they want your review as a backup. It seems rude to ask and probably usually is, but I’ve twice agreed to review manuscripts for journals only to be told after I’d agreed but before the deadline that they had received a sufficient number of reviews and no longer needed mine. This doesn’t seem polite except under extraordinary circumstances and wasted hours of my time.

- Read over the journal’s criteria for judging manuscripts. For some journals, novelty is unimportant, or there’s no requirement to work with empirical data. It’s really annoying to be held to standards that the journal itself does not endorse; the editors often don’t appear to recognize when this is happening. (Nope, no baggage here!)

- Start your reviews with a succinct summary of the manuscript, placing it in the context of other work in the field. This helps the editor, who might not understand the paper so well, and also shows that you understand the paper. Directly discuss what the paper contributes or could contribute and the extent to which the paper satisfies the criteria important to the journal.

- Next review the major strengths (sic) and weaknesses of the paper. Be very clear about what makes and/or doesn’t make the paper convincing.

- Give evidence for your views. Especially regarding claims of novelty, cite! One of the most maddening things is to get a review saying, “Yawn, this has basically been done before,” with no references. Citations also help the authors improve their work quickly, especially if you’re suggesting relevant papers they’ve missed.

- In general, do not punish the authors for not doing the study you would’ve done or think should be done. Focus on what the paper does contribute or could contribute with minor or moderate changes.

- Do not recommend acceptance, major revisions, minor revisions, etc., directly in the body of the review. That recommendation is for the editor to make. Your job is to help the editor make a decision and the authors to understand your impression of their paper—both what’s good about it and what can be improved.

- Be constructive. Never be snarky or sarcastic or impugn the motives of the authors. Imagine this is the first review the first author is receiving, or that the authors have feelings.

- Let the editor know in your review or confidential comments if you do not feel qualified to judge certain parts of the manuscript. It is okay to state this in the main body of your review too. Just remember you have a positive duty to disclose.

- Especially for papers that need a lot of work, it’s not a good use of time to note every small mistake. You do not need to be the copy editor. If there are small technical mistakes, e.g., the lines on a graph are switched or the notation is messed up, put them in a section for minor comments.

- For papers involving code, try in 10 min to run the code and check its documentation, but do not reimplement the analysis unless you want to. You also do not need to check complex mathematical derivations. However, the methods should be clear and completely reproducible from the content of the manuscript. (I am not a fan of “See previous papers \(X_{t_1}\), \(X_{t_2}\),…”, though a bit is okay.)

- It’s fine, even good, to comment on other reviewers’ comments in later rounds of review, especially if you disagree with them. If you think a reviewer has made a major error, email the editor.

- Peer review can take a long time, sometimes more time than is worth it. Please check with me about how much time to spend on peer review before accepting an assignment.

4.12 Have productive meetings

4.12.1 Research meetings

Before the meeting:

Make sure every meeting has a purpose that everyone understands. It is good if you can send an agenda beforehand. Some people also like to review materials, such as summaries, beforehand. Ask they want this. If someone requests a meeting with you, it is also completely fine to ask what the agenda or objectives will be.

If proposing an ad hoc meeting, give an estimate of how much time it should take in your invitation. This will help people focus during the meeting.

If the meeting is routine, let the other participants know in advance if you expect it to be especially short or long.

Send a formal calendar invitation for the meeting. You might need to ask especially senior participants who do not “accept” the invitation if they need a meeting reminder. I dislike meeting reminders.

At the meeting:

Quickly review the meeting’s purpose and agenda.

If discussing research, ensure you give appropriate background information and context, and ensure your figures and numbers are clear (even if they’re not “pretty”).

Take notes rather than forcing yourself to recall things later.

End by summarizing the next steps, responsibilities, and timeline.

Keep the meeting on track: If a less relevant discussion takes off, flag this as a topic to address later.

After the meeting:

For committee meetings, meetings with collaborators, etc., send a short follow-up email summarizing what was decided and what will happen next. For meetings with me, tasks should be updated in Asana, and additional notes can be there or in your lab notebook.

Follow up on those commitments.

4.12.2 Seminar speakers

Try to meet with seminar speakers who do relevant work. This is just fun, and it also helps people get to know you and your research. Think of their visits like an intermittent conference without the annoying travel. Prepare for the meetings by reading at least one of their papers, skimming their other works, and writing a list of questions that would be fun to discuss. If you’re having trouble getting on the schedule, let me know.

4.13 Book travel

The general idea is to reduce costs as much as possible while remaining comfortable and productive. (These savings will go toward more travel, research, and fun lab things.) The grants that fund travel have different allowable expenses and documentation requirements, so please check flights and your total budget with Jessie before booking.

Guidelines:

- Please plan your travel far enough in advance that we are not paying through the nose for registration or flights. Please book flights at least six weeks in advance, unless you’re really confident the price is dropping. For conferences, book flights earlier.

- CEIRR and CIVIC are contracts that generally do not support conference participation: all travel must be in direct service of the research, e.g., trips to work with collaborators in the consortium. All travel for CEIRR and CIVIC must be approved in writing by the center at least a month before the travel occurs. Please talk with Jessie and me well in advance if you are CEIRR/CIVIC funded and want to travel.

- We are generally required to book travel through the Fox Travel Agency through a University portal. Jessie can book the flight and hotel for you so you do not have to pay and then be reimbursed. If you pay upfront yourself (this is generally frowned on), you will have to wait until after the travel is complete to be reimbursed.

- If you book an atypical flight, such as something arriving a few days early or leaving a few days late, or that includes personal travel, funding groups generally require that you also include a quote, obtained at the time of booking, of the cost of the flight for typical (business-only) travel. They’ll only reimburse up to this amount. But it’s otherwise totally fine to include personal travel with business, as long as you document carefully.

- If your travel is funded by the federal government, you generally must fly with a U.S. carrier or book your ticket through that carrier.

- You are not required to share hotel rooms or use Airbnb, but if you do, it’s appreciated.

- It’s also great if you can share rides/taxis and take public transit, but you’re not expected to go to great inconvenience to save money.

- The University will reimburse only original itemized receipts; it will not give you a per diem. Food costs are reimbursable up to federal rates if covered by a federal grant, or $100 if from a non-grant account, per University policy. CEIRR and CIVIC meetings do not reimburse for food. I think the principled thing to do is only submit receipts for food costs above what you’d normally spend (and not to go crazy with spending). Note the receipts must be itemized, and alcohol cannot appear on the receipts of NIH-funded travel.

- Internet charges cannot be expensed to federal grants.

- Submit receipts to Jessie within three weeks of travel. Her deadline to submit receipts is one month after travel. If she’s away, submit receipts more promptly.

- I suggest you sign up for airline loyalty programs if you haven’t yet. Southwest and United are the University’s preferred airlines, and they will often be cheapest.

4.14 Be happy doing research

But I am very poorly today & very stupid & hate everybody & everything. One lives only to make blunders.— I am going to write a little Book for Murray on orchids & today I hate them worse than everything so farewell & in a sweet frame of mind, I am

Ever yours

C. Darwin

If you’re excited to solve the problems you’re working on and to communicate them to the world, research is great. Sometimes things can get in the way. Major obstacles and tips to avoid them are below. If you think something is missing from this section, please let me know or add it.

4.14.1 Time management

A critical skill is to identify your priorities, understand how you work, and learn how to allocate your effort to get the most important things done and avoid overburdening yourself. The National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity has excellent materials, designed for faculty but relevant for everyone, on helping you use your time well. You should be able to get free access to the videos and tools through the University. If you’re regularly feeling overwhelmed by tasks or unhappy with your progress, this is also something we can discuss at weekly meetings. As mentioned, I think 40 h of carefully chosen, focused work per week (excluding breaks) is enough to get things done.

Practical suggestions:

- I use the Freedom app and Pomodoro Technique when I’m having trouble focusing or really resisting some task. Often when I’m resisting a task there’s some emotion behind it (e.g., not wanting to be bored), and recognizing that emotion and setting a timer (I can handle 20 min of boredom) helps me avoid procrastination. It’s important to realize you can feel all sorts of things and achieve your goals anyway.

- Every important task or task >5 min goes into Asana and immediately placed on my calendar. This helps things get real. It’s harder to be deluded about how much time I have.

- I find it useful to compare my scheduled day to how I actually spent my time. It has made me realize the necessity of adding a bit of extra time for spontaneous meetings, scheduling brainless tasks after teaching, etc.

- I also give myself weekly and quarterly goals, and do the same comparisons.

- Working or accountability groups/buddies can be great. If you know others who are struggling to read, write, etc., regularly, consider setting up formal work sessions or accountability reports. The buddies don’t have to be local.

4.14.2 Imposter syndrome

It’s really common and can’t completely be cured, but you can decide not to care about it. My best advice is to practice acknowledging doubt and then moving on to whatever you want to do. (I like this post from psycgirl.) Because research involves working on unsolved problems with an ever-expanding set of tools, and the world is complicated, we have to be comfortable pushing through the discomfort of ignorance, failure, and mediocrity (Schwartz 2008). Once you accept this, it can mostly be fun to work on interesting problems with great people.

In general, you should not conflate your or anyone else’s confidence and competence (see the Dunning-Kruger effect). This is important in making science more equitable.

4.14.3 Mental health and medical problems

Please take a “mental health day” if you need one, and if you feel stuck, I encourage you to consider talking to a therapist. If you are new to therapy, keep in mind that there’s enormous variation in quality and style between therapists. If you don’t feel like you’re making progress with a therapist, find a new one. Remember that many University health plans cover therapists who are not on campus. Of course, there are a bazillion ways to maintain our mental health, and I encourage you to develop multiple strategies if you’re feeling strained.

If you’re not getting good medical care or you have a condition that interferes with your work, please let me know so we can find better care and/or accommodate your needs.

4.14.4 Unwelcome environment

If your environment is creating difficulty, e.g., the University or lab does not feel like a welcoming place, or you are under great financial strain, please let me know. Your workplace should obviously be supporting you.

A note to students: Under Title IX, if you speak with me about sexual misconduct, I am required to talk to the Title IX Coordinator about it. The University may proceed with an investigation (potentially despite your wishes). If you wish to maintain confidentiality, there are a variety of people you can talk to.

4.15 Give a good talk

I like this advice from Jonathan Shewchuk and this outstanding advice from Rachael Meager (applies to writing papers and grants too). If you’re scared to get started, read Tim Urban’s essay about his TED talk for inspiration. If it’s the first time you’ve given the talk, sign up on the lab calendar to give a practice presentation at least a week before the talk itself.

4.16 Interview someone

We have frequent opportunities to meet with potential hires, especially prospective graduate students, postdocs, and faculty. These are usually great opportunities to talk research with someone new, but they’re also critically important from an institutional perspective. You play an essential role in helping identify top performers. We want colleagues who will not only do great work but who will make the lab, department, etc., a more invigorating place to be. Please take advantage of opportunities to meet with people and learn about what they do. You can take it as read that whoever is doing the hiring wants feedback promptly: provide comments (in person, over the phone, or in writing) quickly, e.g., <24 h. Please also let me know if you think particularly great people are on the market! We generally need to act quickly.

It’s vitally important to decide before we meet a potential hire what criteria we should use to judge them: studies show that we often subconsciously rationalize biases by identifying criteria post hoc. I think academics in particular are prone to discrimination because their self-identity is so predicated on objectivity. It is useful to have a core, fixed set of questions or topics to discuss with different candidates. This doesn’t mean the conversation can’t wander, but it promotes fair comparisons.

I often ask the following of potential lab members:

- Why do you want to work in this field? Can they name problems they find interesting? Shifts in methods or recent findings that make them particularly excited?

- Which papers have particularly influenced you? We want people who understand the scientific context for their work and have gone beyond the NYT articles, Tweetorials, assigned reading, etc. They should be able to discuss papers related to their research interests that they have found themselves or in the course of voluntary research, rather than coursework.

- Why do you want to join our lab/department? Why do you want this job? They should show discernment and some thought about the culture they are looking for. They should be able to describe how our expertise intersects with their goals. Their meta-goal should be producing high-quality research/papers.

- What does your ideal day or week look like? It should involve mostly research and fairly independent work, not mostly meetings, but they should also want scientific exchanges and inspiration from a fast-paced scientific environment.

- How would you go about solving [a recent research problem]? This is a good opportunity to test their skills. Are they thinking about the problem logically? You can also ask about their background in reproducible research, programming, math/stats, etc. Remember that pretty much no one starts with a perfect background in everything.

Additionally, I pay attention to

- whether I can discuss scientific concepts easily with the candidate.

- whether they ask me good questions about our work vs. questions that could have easily been answered through a quick search.

I also spend a lot of time aligning expectations about their potential future role.

Remember again that the purpose of the interview is two-fold, in that it’s also an opportunity to bring great people into the lab. If this appears to be a good fit, I explain why.

Please keep in mind that many laws exist to protect people from discrimination, and they affect what potential employers can and cannot ask interviewees. Even though you might not have hiring authority, as a representative of the University, you should avoid asking these questions too, even indirectly. (You might not have any intent to discriminate, but the questions could rattle the candidate, and others who hear might be inappropriately influenced.) Do not ask questions about race, color, national identity, or citizenship; religion; sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation; pregnancy status, marital status, or parenthood status; disability; veteran status; and age. For instance, do not ask about what languages someone speaks (unless it is somehow relevant to the position, which it usually isn’t), their accent, where their parents were born, or their partner’s job, or the existence of a partner. It is especially inappropriate to bring up two-body issues when discussing candidates until an offer has been made. Questions related to economic status (e.g., car or home ownership, debt, etc.) are also unwise.

The basic principle is equity. Equity is a moral imperative. It also has the handy feature of broadening the talent pool for any position and probably accelerating the pace of science. From this principle, it follows we should not discriminate or draw conclusions about scientific and professional merit based on a huge class of dumb things, like whether someone wears makeup, seems really excited about sports, programmed in Fortran at age 3, knows your friends, drinks socially, etc. We should make an effort to work well with people who are different from us.

I have heard almost every type of inappropriate interview question in academia. It’s pretty sad. If you hear someone asking one of these questions, do your part by telling the candidate they don’t need to answer and/or immediately changing the topic of conversation. Candidates will often answer these questions anyway or even volunteer protected information on their own. Do not follow up, and attempt not to be influenced by the information.

4.17 Contribute to the handbook

I’d love to make the handbook as useful as possible. Please contribute if you see ways to improve it (especially if you have css skills!). The handbook repository is in the lab’s github account. Submit your changes as a pull request. If you’d like to make many contributions, let me know, and I’ll add you as an owner.

4.18 Win at conferences

There are a bazillion resources on this. I think they boil down to

- Try to develop a list of people you’d like to talk to before you go, and have an idea of what you’d like to discuss with them. It can sometimes help to send an email in advance if there’s someone you really want to connect with. You can set up a time and place to meet. Happy to discuss.

- Pace yourself. Get sleep. Go to talks, but not necessarily all of them. Make time for dinner and socializing. Ask people to join you for dinner.

- Practice asking speakers questions.

- Get in the habit of introducing yourself, asking people about their research, etc.

- Avoid spending much time with lab members. Really, the opportunity cost of hanging out with lab members is big. Meeting new people might not always feel like it amounts to much, but it will pay big dividends, I promise. You’ll see many of them again. You’ll probably collaborate with a few.

- It’s not (just) you: scientists are awkward.

4.20 Engage with the public

Locally: The University has established relationships with local schools through the Neighborhood Schools Program.

And beyond: Check out the OpEd Project and please let me know if you’re interested in talking to reporters about particular topics.